Behavior Today Newsletter 40.4

From the President’s Desk

Timothy Landrum

Time flies, I’m told, and writing this President’s Message reminds me of that in a couple of different ways. First, it still feels to me like the CEC convention in Louisville (where I live and work) has barely concluded. As I noted in my last message, the DEBH presence at CEC was outstanding, and I’m thankful for all who attended, presented, and participated in our Executive Committee meeting (and social). But, while it feels to me like CEC 2023 is just-concluded, time does not stand still, and members should note that planning for CEC 2024 in San Antonio is already well underway. Watch for more details in communications from us via email, social media, and on our website—but note especially this date: Monday, June 5, 2023, which is when most regular proposals are due to CEC. Next year, we hope to have another outstanding slate of DEBH sessions, so please mark this date and be sure to submit your best proposals!

A second reason I’m aware of the passage of time is that I believe (if I understood Behavior Today editor Staci Zolkoski correctly…) this is the final time I have the opportunity to write an update for this newsletter as DEBH President, as I transition out of the role on July 1. This seems very odd to me, as it feels like my time with the Executive Committee has barely begun. The good news, for me anyway, is I’ll still have another year to serve the DEBH Executive Committee as Past President. One of the roles of past president is to support our Nominations and Elections Committee, which has done an outstanding job in recent years. That’s evident in the officers ready to move into new roles, including incoming President Robin Ennis, who will be followed by Lonna Moline, and then Chad Rose. In other words, DEBH is in very good hands, and the work we are engaged in will continue. As I transition, I’ve promised our EC one area I want to remain involved in involves our exploration of some new DEBH publications (also mentioned in a previous newsletter; more on that as the effort evolves).

The publications initiative, as you may recall, is one of the activities we’re exploring in regard to the larger effort toward strategic planning we have been engaged in this academic year. Following some initial brainstorming sessions, both in person and virtual, and with a focus on our mission statement, we have begun to flesh out possible activities and initiatives that can move us toward meeting our mission, specifically around three strategic targets:

- Disseminate and promote resources that increase awareness of effective data-informed practices.

- Engage in advocacy

- Enhance diversity, social justice, intersectionality, and contextual understanding

Obviously, the publication effort is but one strategy aligned with target #1, and please note, this won’t happen in a vacuum. On our last call, the EC agreed a next step will be to seek direct input from members on the framework we are developing. That is, while we are building directly on the slightly updated mission statement members approved at the Louisville convention, we want a continuous loop of input and feedback from membership as we craft our division’s agenda for the coming years. We’ll also need significant support as we work on the agenda. Watch for more on this and all fronts in the coming months, perhaps from me, but just as likely from new members of our EC (or those assuming new roles), especially as they transition into their new roles this summer.

Finally, speaking of time flying, if you’re in a role that provides some sort of summer break, and maybe especially if you’re not, I hope the soon-to-arrive summer brings some measure of fun, or down time, or at least small moments of rest, rejuvenation, or peaceful distraction. I hope those are helpful as we embrace and engage in all the important work that lies ahead.

-TJL

My Most Memorable Student: Voices from the Field

Jim Teagarden & Robert Zabel, Kansas State University

The Janus Oral History Project collects and shares stories from leaders in education of children with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD). The project is named after the Roman god, Janus, whose two faces look simultaneously to the past and future.

One Janus Project activity is recording and sharing educators’ descriptions of memorable students. They are asked: Who is your most memorable student? What did you learn from this student? How has the student impacted your career or life? What follows is the story of Kelly as told by Sheldon Braaten.

* * * * *

Only if I Want To

By Sheldon Braaten

His name was “Kelly.” He would have been fifteen at the time. We had written an intervention plan, a treatment plan, for Kelly and the skills he was to learn. He proceeded to teach us that we were incapable of teaching him anything. He was sent to me for offenses he committed which I don’t recall. I showed Kelly his treatment plan, and he wasn’t the least bit impressed by it. So, I pulled a blank form out of my desk since I had just printed a bunch of them. I handed him it to him and said, “Well, Kelly, you write the treatment plan, and if it makes sense, we’ll do it.” He promptly rolled it up into a ball and threw it at me. So, I reached in my draw, pulled out another form and handed it to him. I repeated, “Kelly, you write the treatment plan, and if it makes sense, we’ll do it.” He rolled it up into a ball, threw it at me, and said “F…k you.” So, I again reached in my draw, pulled out third form, handed it to him and said, “Kelly, you write the treatment plan, and if it makes sense, we’ll do it.” This time, he didn’t say anything, but he kept it. The next day he came back, and he had written some things on it. I read them, and I said, “Kelly, I think we can do this.” So it began—kids telling us what made sense to them.

Kelly taught me to ask the kids. I think that’s something we don’t often do because we think we know better. I now do a lot of training around the country, and I use a quote from a kid. This is a kid in a juvenile justice facility who said, “I must die…everything else is only if I want to.” There’s something strong about that statement. Pay attention—Kelly taught me that in 1976.

* * * * *

This story is a part of the Midwest Symposium for Leadership in Behavior Disorders video series, “My Most Memorable Student.” Dr. Braaten’s video is available at: https://archive.org/details/SheldonBratten319. More than 40 teacher stories of their memorable students can be viewed at: http://mslbd.org/what-we-do/educator-stories.html.

Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools

Mitchell L. Yell

On March 21, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a unanimous ruling in Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools. In the 9-0 ruling, which was written by Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, the High Court reversed and remanded the case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit for further proceedings based on the Supreme Court’s opinion. To read the decision, click here.

The case involved Miquel Perez, a deaf student, who filed a lawsuit under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) against the Sturgis Public Schools in Michigan for failing to provide him with a qualified sign language interpreter. Miquel had filed a due process complaint against the Sturgis Public Schools, but before the Michigan Department of Education could hold a hearing, the Sturgis school board settled Miquel’s claim.

The Perez’s then filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging the Sturgis school district failed to provide Miquel with the resources he needed to fully participate in school, which violated the ADA. The federal district court dismissed Miquel's claim finding he could only file his lawsuit after exhausting administrative remedies under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Essentially, the district court dismissed the lawsuit because Miquel had accepted a settlement agreement rather than going through the IDEA's administrative proceedings, which includes a due process hearing. The case was appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit, in which a divided panel upheld the ruling of the lower court.

In an 8-page opinion written by Associate Justice Gorsuch, the Supreme Court reversed the ruling of the 6th circuit court. Justice Gorsuch wrote that the IDEA requires plaintiffs who file a lawsuit under another federal law to exhaust all administrative procedures outlined in the IDEA only when they are seeking a remedy the IDEA also provides. Because the IDEA does not include monetary damages, Perez's lawsuit seeking compensation for emotional distress and loss of income, was not subject to the IDEA's administrative exhaustion rule. Thus, if a student’s parents sue a school district for monetary damages under the ADA because the district failed provide a FAPE, in accordance with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Perez, the lawsuit is now allowable. After the Supreme Court's ruling, Miquel Perez will no doubt continue to pursue his legal claims under the ADA.

What might this case mean? Some school officials believe the ruling will result in increased litigation because it injects the possibility of monetary damages. However, successfully suing for monetary damages under either the ADA or Section 504 is a high bar. Parent advocacy groups, on the other hand, believe the ruling may make schools more likely to negotiate in good faith because they may not be protected from the threat of lawsuits seeking monetary damages. Only time will tell what the effect of this ruling will be. I doubt teachers or administrators will see any changes on the ground resulting from this ruling.

USA Today published an excellent article summarizing the case that includes a picture of Miquel Perez (who is now 24 years old). You can read the USA Today article by clicking here.

You can hear the oral arguments in the case at Oyez.com and read about the case, including proceedings, orders, and friend of the court briefs at SCOTUS blog.

“Schedules of Reinforcement Across Work, Life, and Leisure”

Eric Alan Common, Ph.D., BCBA-D, University of Michigan-Flint

Recreational Reinforcement is a column highlighting the recreational and leisurely pursuits of educators and professionals while also making connections and offering illustrations and examples related to applied behavior analysis. This month’s column highlights schedules of reinforcement and offers brief definitions and examples geared toward spring and summer! This column is dedicated to Dr. Erin Fitzgerald Farrell co-editor of Recreational Reinforcement, who is enjoying a brief post-reinforcement pause after successfully defending her dissertation in April.

Keywords: schedules of reinforcement, extinction, summer holiday

2022-2023 Call for Columns:

Recreational Reinforcement is a bi-monthly (6/year) column dedicated to discussing recreational or leisurely pursuits, making connections, and offering illustrations and examples related to applied behavior analysis. The only rule is nobody wants to hear about work being your “recreational reinforcement.” Please send submissions or inquiries to Dr. Eric Common at ecommon@umich.edu. Directions for submissions: (a) article title, (b) names of author(s), (c) author’s affiliations, (d) email address, and (e) 700-1500 word manuscript in Times New Roman font. Bitmoji, graphics, tables, and figures are optional.

“Schedules of Reinforcement Across Work, Life, and Leisure”

Schedules of reinforcement refer to the relationship between reinforcement delivery (e.g., patterns or frequency) and the effect reinforcement density has on future behaviors (e.g., the strength or persistence of behavior. On the one hand, we can conceptualize schedules of reinforcement along a continuum of no reinforcement (e.g., extinction) to continuous reinforcement (e.g., continuous reinforcement schedule). Continuous reinforcement, if not shifted to an intermittent reinforcement schedule, will lead to a rapid decline (e.g., extinction) of the behavior once reinforcement is removed (or if the density of reinforcement delivery is weaned intermittently too quickly). Extinction, at the other end of the spectrum, refers to procedures that cease providing reinforcement for previously reinforced behaviors.

When delivering reinforcement along the continuum heading away from extinction, schedules of reinforcement can be delivered continuously or intermittently. Continuous reinforcement schedules are best used when establishing new behaviors or maintaining already established behaviors as part of a booster (e.g., before or after a winter break for example). Intermittent reinforcement, on the other hand, is when a target behavior is reinforced only sometimes or at certain times, which can be useful for maintaining a behavior over time and reducing the likelihood of extinction.

There are four types of intermittent reinforcement schedules: fixed ratio, variable ratio, fixed interval, and variable interval (Cooper et al., 2020).

- Fixed ratio reinforcement schedule delivers reinforcement after a fixed number of target behaviors have been exhibited, which can lead to a high rate of behavior but also a post-reinforcement pause.

- Variable ratio reinforcement schedule delivers reinforcement after a varying number of target behaviors have been exhibited, which can be highly effective in maintaining a behavior, but also unpredictable and hard to extinguish.

- Fixed interval reinforcement schedule delivers reinforcement after a fixed amount of time has elapsed since the last reinforcement, which can lead to a post-reinforcement pause and low rates of behavior until the reinforcement is imminent.

- Variable interval reinforcement schedule delivers reinforcement after a varying amount of time has elapsed since the last reinforcement, which can be highly effective in maintaining behavior and promoting consistency, but also less predictable and less potent than continuous reinforcement.

How might you use an intermittent schedule of reinforcement this spring or summer?

- A family planning a road trip might develop a fixed ratio reinforcement schedule by letting their children select a half-day activity at a pre-selected designation after completing a fixed number of assigned chores, such as mowing the lawn or cleaning up the car.

- A group of friends on a fishing trip are likely to experience a variable ratio schedule of reinforcement, in which there will likely be an unpredictable number of casts or attempts before the thrill of catching a fish.

- Teachers often have the choice of dividing their contract months over a 12-month period; this ensures their salary is delivered on a fixed interval reinforcement schedule (e.g., paid every two weeks).

- A new pet owner might develop a variable interval reinforcement schedule with their puppy by delivering praise for good behavior at random intervals toward the conclusion of the training series.

Whatever your summer plans are, wishing you a restful, productive, and ultimately enjoyable spring and summer! And remember, there are established potential drawbacks and benefits for each and every schedule of reinforcement – be mindful in your practice and homelife and reinforce the ones you care with intentionality.

References

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis. Pearson.

Author’s Bio

Eric Common is an Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan-Flint in the Department of Education and is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral Level

Dear Miss Kitty: Advice Column

Miss Kitty

Dear Miss Kitty:

I was a veteran special education teacher until January of this year. I had taught a cross categorical class at the middle school level for twelve years in the same school. I had always received an excellent rating and prided myself in the work I did with my students. I had a community service program that worked well. My previous principal retired at the end of last year, and our school got a new principal along with a new school superintendent. I have really tried to figure out why the new principal did not like me, but he did not. He made me eliminate my community service program because he said my students had no business going out in the community. He would come into my classroom at least twice a week and announce that he did not like what I was doing with my students. When I tried to talk with him, he told me I should have all the students doing work at grade level. When I explained some of my students were behind in academics, he told me to get them caught up.

I could go on, but the pressure was so hard on me, I could not take it anymore, and I resigned. My husband was supportive because he saw that I was emotionally a wreck. I really believed I was a terrible teacher so looked for another job outside education. I got a job in a law office because I thought I might become a paralegal. However, my heart was not in it, and I really miss teaching. Now I heard the principal was let go. I don’t know what to do. Should I try to return to my school? They had a substitute the rest of the year so my job might be available, or should I look elsewhere. I am torn as to what I should do.

Heartbroken Hanna

Dear Heartbroken Hanna:

I am so very sorry to hear about what happened to you the first semester and the pressure was so great you needed to resign. It was important for you to take care of yourself. It is also important you recognize you had 12 years of successful teaching and you can celebrate that. It also sounds like you have realized you don’t want to pursue a career as a paralegal.

Do you wish to return to teaching this year or do you want to take more time to pursue other avenues or continue to rebuild your emotional health? If you wish to return to teaching this next year, consider these factors:

- If you really want to go back to your previous classroom, you need to talk with either the superintendent or the personnel director, whoever it is in your district who is responsible for hiring, to see who may be hired as principal. Is the superintendent returning to the district? What is his or her philosophy about special education? You may want to wait until the hiring decision for the principal is made and then talk with the new principal if he does the interviewing to see whether his philosophy about working with students with special needs is the same as yours. You also want to make sure the district will give you your years of service on the salary schedule because they may try to put you back at the beginning of the salary schedule because you left.

- Also do your homework to find out what is going on in the district about support for teachers. Talk with teachers in other buildings in the district to see if the superintendent has a positive vision for the district.

- When you left, did you tell the administration why you left or put it in writing. It may come up about why you left, and you don’t want to make negative comments about the previous principal but would probably want to say that you needed some time away or that you had a different point of view from the principal. Depending on the size of your district and school, I imagine that word travelled about why you left the school without you needing to be negative about the man. You have your reputation to preserve so want to maintain a high level of professionalism.

- If you do your homework and feel uncomfortable that a new principal might have the same philosophy as the previous principal had, then consider going to another district. The job market for special educators is excellent and you want to make sure you are offered a position that will meet your needs. For example, you will want to find out the numbers on your caseload, whether you would be able to do community service, what the principal’s philosophy pertaining to special education is. Yes, salary is a factor but what is important is administrative support and your sense of belonging in the school environment.

- There is another possibility you might consider if you are just still unsure what you want to do or want to make sure that you are not getting into a difficult situation. Have you thought about substituting? There is a shortage of subs and by doing this, you can see what the climate is in different school buildings and get an idea of where you might want to apply for a permanent job.

These are just some factors you want to consider. Your emotional health is important, and you may have lost some of your self- confidence, but remember you are a good teacher and have a lot to offer. You want to get in a situation where you will receive the credit you deserve so do your homework to find the best solution. Students need you and you need a position that values your expertise.

I wish you the best,

The Seesaw of Motivation and the Function of Behavior

Doris Adams Hill, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA & Theoni Mantzoros, PhD, BCBA (she/her)

Special educators are often considered the experts in their school when it comes to developing functional behavior assessments (FBAs) and behavior intervention plans (BIPs) for children with problem behaviors, yet rarely are they trained much beyond basic antecedents, behaviors, and consequences (ABC’s). Fully developed FBAs and BIPs are required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The concepts introduced in this piece go a little further, adding motivating operations (MO’s) that include establishing and abolishing operations (EO’s and AO’s). Knowledge of these concepts can enhance a teacher’s ability to provide evidence-based interventions and more fully developed behavioral interventions for the students they serve based on behavioral function (Hill et al., 2020).

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other developmental disabilities often engage in high rates of problem behaviors (Hill et al, 2020; Koegel, et al., 1995). The topography, or what the behavior physically looks like, often varies across individuals. Additionally, the purpose of a behavior may mean different things depending on what the individual gets out of it (function or purpose-why is he/she doing that). The specified functions can include access to an item or activity; attention from others; escape from a task; or sensory reinforcement, which typically means that engaging in the behavior is usually reinforcing (like humming a tune). The acronym EATS describes the four purposes of engaging in a given behavior (escape from a task/person, attention, access to tangible items, and sensory needs). MOs describe why an individual engages in the behavior at certain times and not others based on the value of the reinforcement (reward). Additionally, understanding why the individual is engaging in a problem behavior allows the educator to teach a replacement behavior, which then allows the individual access to the hypothesized reinforcer via a more socially appropriate path. For instance, if an individual is grabbing toys from others to gain access to the items, teaching the student to take turns, wait a specific amount of time, request appropriately, or access a different toy are all more appropriate replacement behaviors. Effectively utilizing the function of the behavior is essential to long-term positive educational, behavioral, and social outcomes (Carbone et al., 2007). Understanding why the value of engaging in a certain behavior is stronger at certain times is also important (Hill et al, 2020).

Most special educators are introduced to behavioral principles in their undergraduate (and certainly graduate) classes. Understanding the function of a behavior (why it occurs) is key to developing interventions to change and replace challenging behaviors that impact educational progress. Why is this important to special educators? IDEA and its amendments mandate a BIP be put in place for students with disabilities and challenging behaviors that impact educational progress (Yell, 2012), but rarely do teachers understand the need to go beyond the ABC’s of behavior when developing these plans (Hill et al., 2020). Conducting the FBA is also required when a student in special education is suspended for more than 10 days or placed in an interim alternative education setting (IAES; Yell, 2012; IDEA, 2004).

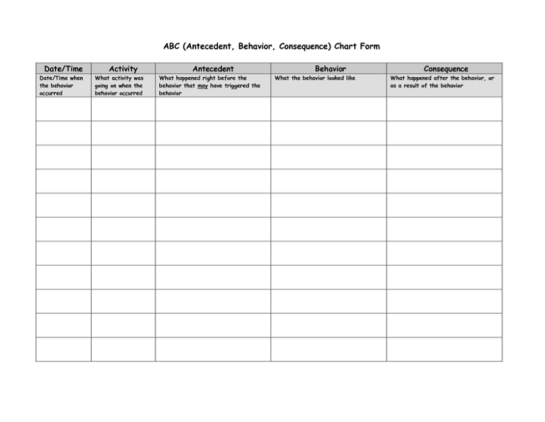

Table 1

ABC Chart form

The FBA is a multi-step process that may include some or all of the following:

- records review

- parent and staff behavioral interviews

- student interviews, if appropriate

- the completion of rating scales assessment

- direct observation of the student in the problem activity/setting

- A-B-C or scatterplot analysis conducted by staff

- And, if necessary, functional analysis.

At times, however, when a BIP is unsuccessful, it may be necessary to move a step beyond the ABCs of behavior or the three-term contingency, and work to enhance our understanding of how a fourth component of the contingency may further impact the ability to comprehend functions of behavior. MOs are a critical component to the ABC sequence as they alter the value of a consequence and, therefore, alter the dimension of an individual’s behavior. For instance, determining that a student engages in aggression to gain access to a food item, would follow that the level of hunger for the student would increase or decrease the motivation to gain access to the food. In this scenario, an individual will be less likely to engage in the aggression if he or she just ate a filling lunch. Additionally, going for a prolonged period of time without access to any food items may effectively increase motivation to gain access to the desired items. For this individual, therefore, this would increase the behavior in which they engage to gain the food (because the value of food has increased with hunger), therefore increasing some dimension of aggression.

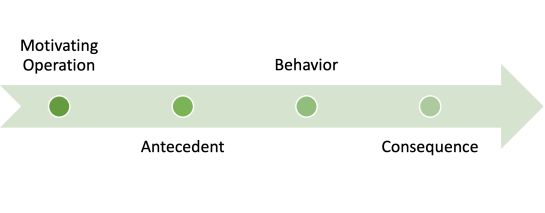

Figure 1.

The chain of behavior including Motivating Operations (MO’s)

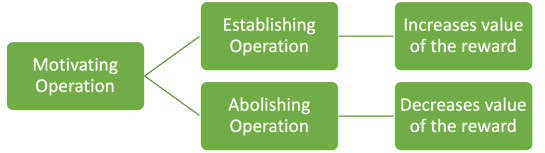

In the sequence of ABCs, MOs precede the three-term contingency, thereby, creating a four-term process. There are two main types of MOs, including establishing operations (EO) and abolishing operations (AO). An EO increases the value of reinforcement in force or intensity, while also increasing the dimension of how the individual will respond. The AO lowers the value of reinforcement in force or intensity, therefore lowering the dimension of how the individual will respond (Cooper et al., 2019; Ivy et al., 2016; Michael, 1982). For example, if an individual engages in self-injurious behavior to gain access to attention from his teacher, the EO will be present when the student has gone a prolonged period of time without attention. The lack of attention from his teacher will increase the value of attention, causing the individual to attempt to gain access, and in this case by engaging in self-injury. If, however, the teacher effectively gives attention to the student every few minutes, this would set up an AO as the student has frequent access to the attention and does not need to engage in self-injury to access it. Understanding MOs, therefore, strengthens our ability to determine the “why” of behavior, especially when there are inconsistencies in the behavior across time and allow for a more precise selection of the timing and type of reinforcement utilized in a BIP.

Figure 2.

Motivating Operations as they relate to Abolishing and Establishing Operations.

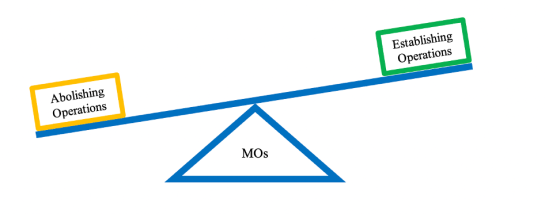

Figure 3.

The Seesaw of Motivating Operations

Note: EOs and AOs move back and forth as need changes the value of the reward.

Table 2 Examples of the four-term contingency.

| MO (EO/AO) | Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence | Possible Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Just finished lunch (AO) | Teacher offers goldfish as reinforcer for DTT (discrete trial teaching) | Student knocks goldfish and DTT materials off desk. Flops to floor | Teacher offers use of playdoh as reinforcer | To escape DTT since goldfish were not valued as a reinforcer (goldfish an AO and playdoh the EO) |

| Missed lunch (EO) | At brother’s baseball game, sees hot dog stand | Cries and whines for a hotdog | Parent tells child that is not time to eat yet. Takes child to seat. | To attain a hot dog since food was valued as reinforcement (EO) |

| Just came in from recess on a very hot day (AO) | Teacher tells class to line up to go back outside for a school-wide activity | Student flops on the floor and begins to cry | Teacher asks the paraprofessional to stay with the student until calm | Escape going back outside on a hot day since being outside is not of high value (AO). Value increased for staying inside (EO) |

| Student wants to play outside but must finish math (EO) | Teacher prompts students that they need to finish work (five more minutes) before going to recess | Student begins working faster to finish. | Teacher checks work for accuracy and then praises child. | Student values going outside and finishes work quickly (EO). Student values recess more than escaping math. |

| Individual sees weather forecast (EO) | Looks out the window and sees rain | Picks up umbrella as he/she goes out the door | He/she opens the umbrella | Individual values staying dry when outside (AO for getting wet) |

| Individual’s teacher has been out sick (EO- deprived of seeing teacher) | Teacher walks in the door | Individual runs to teacher to give a hug | Teacher smiles and says “I missed you” | Individual values seeing the teacher after a long absence (AO- sits back down now that individual has greeted teacher) |

| You have been driving for hours and are hungry | You see a restaurant with an “open” sign signaling food is available | You stop to eat | You feel full and are ready to drive some more. | To gain access to food which was valued at that time (EO) but became less valuable once you were no longer hungry (AO) |

| You continue driving and begin to cross a bridge spanning several miles when your fuel gauge light comes on (EO) | You see a gas station sign at the first exit after the bridge so you take the exit | You fill up your tank. | Your tank is full, and you continue to drive. | Getting gas is no longer values as a reinforcement (AO) until the next time you need gas (EO) |

Abolishing Operation

(food has less value)

Establishing Operation

(gas is valued)

Summary

Many special education professionals are responsible for providing individualized instruction for students with disabilities based on the interventions outlined in the IEP. This requires skills that include assessing academic deficits (and excesses) and developing interventions to teach these skills with a goal of reaching grade level performance. With regard to behavior, the special educator is often called to provide expertise in the area of behavior. Understanding more than just the basic ABC’s can help them to develop behavior plans that go beyond the basics of a tree-term contingency and incorporate MO’s as part of an expanded four-term, resulting in interventions that enhance student success and teacher proficiency. It has been the goal of this piece to expand the professional’s knowledge in order to develop more effective intervention plans for students served in their schools.

References

Carbone, V., Morgenstern, B., Zecchin-Turri, G. & Kolberg, L. (2007). The role of reflexive conditioned motivating operation (CMO-R) during discrete trial instruction of children with autism. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavioral Interventions, 4(4), 658-676. Cooper, J., Heron, T., & Heward, W. (2019). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Hill, D., Mantzoros, T., & Taylor, J. C. (2020). Understanding motivating operations and the impact of behavior. Intervention in School and Clinic, 1-4. doi: 10.1177/1053451220914901.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. 1400-1419 (2004).

Ivy, J. W., Neef, N. A., Meindl, J. N., & Miller, N. (2016). A preliminary examination of motivating operation and renforcer class interaction. Behavior Interventions, 31, 180-194.

Koegel, R. L., Koegel, L. K., Frea, W. D., & Smith, A. E. (1995). Emerging interventions for children with autism: Longitudinal and lifestyle implications. In R.L. Koegel & Koegel (Eds.), Teaching children with autism: Strategies for initiating positive interactions and improving learning opportunities (pp. 1-15). Paul H. Brookes.

Michael, J. (1982). Distinguishing between discriminative and motivational functions of stimuli. Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 37, 149-155.

Yell, M. (2012). The law and special education (3rd edition). Pearson.