Behavior Today Newsletter 41.3

From the President’s Desk

Robin Ennis

I hope everyone is enjoying an exciting fall semester. We’re past the midpoint and can look forward to remaining months filled with fun holiday and seasonal activities. When I think of fall, I think of football, cooler days, and the Teacher Educators for Children with Behavioral Disorders (TECBD) Conference. TECBD is time when many DEBH member come together for professional development, networking, and collaboration. This year TECBD is November 16-18 in Tempe, AZ. This year’s conference also will feature virtual Saturday workshops for $35, so if you can’t make it to Arizona, you can still join in the on the great PD options. To register for both in-person and virtual activities, please visit https://education.asu.edu/annual-tecbd-conference

For those of you who can join us at TECBD this year, please note these exciting activities supported by DEBH:

Thursday morning, we will host a breakfast honoring our past presidents of CCBD and DEBH and glean their insight on the future of the organization. If you are a past president and plan to attend, please email past president Tim Landrum (t.landrum@louisville.edu). Immediately following breakfast our executive committee will meet to continue our discussions of activities based on strategic plan.

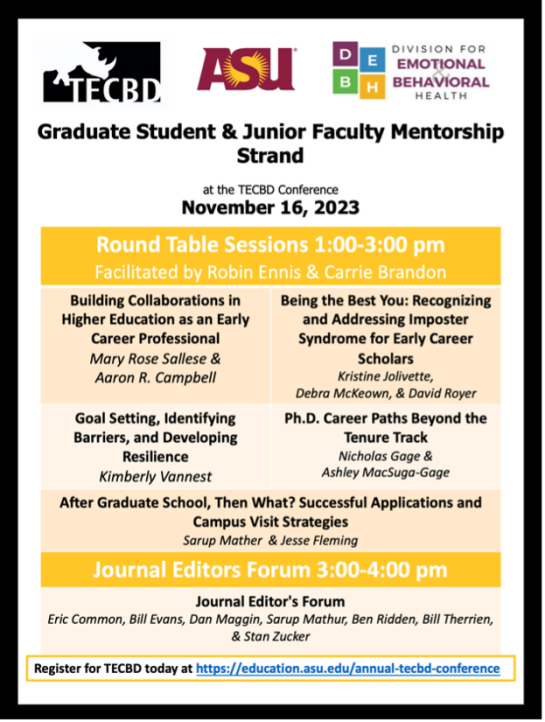

Thursday Afternoon (1:00 to 3:00 p.m.) we will host a mentorship roundtable double session featuring DEBH members, including Aaron Campbell, Nick Gage, Kristine Jolivette, Ashley MacSuga-Gage, Sarup Mathur, Mary Rose Sallese, and Kimber Vannest. See the attached flyer for a description of their session. This session is designed for graduate students, post-doctoral scholars, and early career faculty. Immediately following this session (3:00 to 4:00 p.m.), will be the Journal Editors Forum featuring Eric Common (Education and Treatment of Children Special Issue), Bill Evans (Preventing School Failure), Dan Maggin (Behavioral Disorders), Sarup Mathur (Education and Treatment of Children Special Issue), Ben Ridden, Bill Therrien (Research in Special Education), and Stan Zucker (Education and Training in Autism and Development Disabilities).

Friday morning (9:00 to 11:00 a.m.) our Advocacy and Government Relations chairs, Lee Kern and Sarup Mathur, will be moderating a panel entitled Shifting Perspectives to Inform Movement: Discussing Diverse Approaches to Understanding and Addressing Disproportionality featuring Alfredo Artilies, Aydin Bal, Kelly Carrero, and Adai Tefera. See the attached flyer for more details on this exciting session.

Friday evening be sure you don’t miss the White Rhino, a yearly highlight of TECBD. And you might just find a drink ticket from DEBH in your registration materials.

I’ll close by offering thanks to Heather Griller-Clark and her team at Arizona State University for always putting on such an outstanding program each year. I hope you can join us this year either in person or virtually.

DEBH Foundation & Awards 2024 Announcement

As educators and researchers, fall is a time to start thinking about the upcoming academic year. Is there a project you would like funding for or a professional development opportunity you would like to attend? Additional funds to help pay for your education? The DEBH Foundations & Awards has multiple grants and scholarships. Here is a list of opportunities:

- Guetzloe-Undergraduate Scholarship

- Cheney-Graduate Scholarship

- Bullock-Doctoral Scholarship

- Nelson-Professional Development

- Woods-Practitioner

- Fenichel Research

- Interventionist Research

- Student Interventionist Research

- John Umbreit Doctoral Research Award (JUDRA)

- Leadership Award

- Professional Performance

- Regional Teacher of the Year

| 2023 winners included: | |

|---|---|

| Dr. Eleanor Guetzloe-Undergraduate Scholarship | Tessa Eldrige |

| Dr. Doug Cheney-Graduate Scholarship | Kersten Peters |

| Dr. Lyndal Bullock-Doctoral Scholarship | Danika Lang |

| Carl Fenichel Memorial Research Award | Aimee Hackney |

| Student Interventionist Research Award | Allyson Pitzel |

| Regional Teacher of the Year | Meaghan Bishop |

| Outstanding Leadership | Award Tim Lewis |

This year it could be YOU!

Applications are being accepted now. Below are brief descriptions of the awards and scholarships, including deadlines for submission.

Academic Scholarships

- Dr. Eleanor Guetzloe - Undergraduate Scholarship

- Dr. Douglas Cheney - Graduate Scholarship

- Dr. Lyndal Bullock - Doctoral Scholarship

The purpose of the Academic Scholarships are to support undergraduate and graduate study in the area of emotional/behavioral disorders. The DEBH Foundation will award a $500 scholarship to one undergraduate, one graduate, and one doctoral student towards educational expenses.

Completed applications must be submitted by December 3, 2023.

Carl Fenichel Memorial Research Award

This award competition honors the memory of Carl Fenichel, the founder of the League school in Brooklyn, New York, who was also a pioneer in the education of children with severe behavior disorders. The purpose of the competition is to promote student research in children with emotional and behavioral disorders. This award will be given to students completing research projects, theses, or dissertations in children with emotional and/or behavioral disorders. This includes an award of $500.

Fenichel Scholarship Application

Completed applications must be submitted by December 3, 2023.

Regional Teacher of the Year Award

The purpose of this award is to honor an outstanding teacher who currently works as a teacher of children or adolescents with emotional and/or behavioral disorders based on the area or region of that year's International CEC Conference. The individual should be nominated by someone who is familiar with the nature and quality of his/her work, and who can also speak to the person’s character and their impact on the lives of students with emotional and/or behavioral disorders. This person will receive $500 to put towards attending the National CEC Convention or their classroom.

Nomination for Teacher of the Year

Completed applications must be submitted by December 3, 2023.

Interventionist Awards

This award recognizes higher education faculty who are establishing or have established a coherent line of intervention research with school-age persons with emotional and behavioral disorders (E/BD) in authentic educational environments that improves the outcomes for children and youth, provides teachers/staff/guardians with additional practices, and adds to the field’s body of science. The DEBH Foundation will award $400 (doctoral) and $500 (Higher Education Faculty).

Doctoral Interventionist application

Interventionist Award application

Completed applications must be submitted by December 3, 2023.

Outstanding Professional Performance Award

The purpose of this award is to honor an outstanding practicing professional who works directly with children and/or youth with severe behavioral disorders. The individual should be nominated by someone who is familiar with the nature & quality of his/her work, and who can also speak to the person’s character.

Nomination for Outstanding Professional Performance Award

Completed applications must be submitted by December 3, 2023.

Outstanding Leadership Award

The purpose of this award is to honor an outstanding leader in the field of behavioral disorders who has made significant contributions and has had a significant impact on the field. This individual will have made significant contributions to the field of behavioral disorders through their research; leadership in state, regional, or national organizations; leadership in teacher education or practitioner preparation; or state and national policy development or implementation. The contributions made should extend over a considerable period of time. Nominations should be made by someone who is familiar with the nature and quality of the nominee’s work, and who can also speak to the nominee’s character.

Nomination for Outstanding Leadership Award

Completed applications must be submitted by December 3, 2023.

John Umbreit Doctoral Research Award (JUDRA)

The purpose of this award is to support an outstanding doctoral student to conduct applied behavioral research in their current area of practice. The award honors John Umbreit, who has spent more than 45 years supporting the development of future faculty who are critical thinkers and dedicated to serving children with behavioral challenges. Eligible applicants are those who are enrolled in an accredited doctoral program, actively engaged in applied research to support improved behavior, and have an IRB-approved (or in process) research project in their specialty area.

An award of $1,000 will be presented at the annual Teacher Educators for Children with Behavior Disorders (TECBD) conference in Tempe, Arizona. Award funds are intended to support applicant research activities and/or to present their findings at professional conferences. For information on this award, email awards@debh.net

Completed applications must be submitted August 1, 2024

As you can see, there are numerous opportunities to receive financial support and recognition through the Division for Emotional and Behavioral Health (DEBH).

If you have any questions, please contact:

Sue Kemp sue.kemp@unl.edu

Lexy Langenfeld lexylangenfeld11@gmail.com

Current Foundation and Awards Board Members are here to help you.

Past President- Lonna Housman Moline

Current President- Alice Cahill

Vice President- Sue Kemp

Treasurer- Staci Zolkoski

Secretary- Lexy Langenfeld

General Member- Tia Barnes

General Member- James Lee

New Study Spotlight: Confronting the Silent Impact of Verbal Mistreatment

Eric A. Common

University of Michigan-Flint

Robin Parks Ennis

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Childhood experiences, memories, and lessons from those formative years ripple throughout our lives, influencing our thoughts, actions, and overall well-being. Both minor incidents and significant events from youth can leave lasting imprints, emphasizing the importance of addressing these traumas. Doing so will pave the way for healthier, more resilient futures.

Verbal abuse during childhood, which includes derogatory remarks, insults, and unwarranted criticism, often goes unnoticed. Yet, it leaves lasting impacts. Recent studies have illuminated the broader implications of verbal maltreatment within the realm of trauma and adverse experiences. As our understanding of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), toxic stress, and trauma evolves, addressing these silent yet profound childhood experiences become even more vital.

Recent research has placed a spotlight on this issue, defining and delving deep into the challenges it presents. This form of abuse, though sometimes subtle, plays a crucial role in the wider spectrum of trauma and adverse experiences. As practitioners, families, and those facing these challenges grow more aware of ACEs, toxic stress, and the role of trauma in shaping lives, we realize the urgency in understanding and addressing verbal mistreatment's impact. It is important to note that as a culture we generally think of “big” trauma as the primary culprit (i.e., physical abuse, observing a violent act). In reality, studies suggest that “little” trauma (i.e., frequent yelling, ongoing criticism, neglect) can be just as impactful on the lives of children and their future selves.

The rise in childhood emotional abuse has alarmed professionals and advocates. A recent study by Dube et al. (2023) in "Child Abuse & Neglect" examined childhood verbal abuse (CVA) in detail. The authors reviewed 166 studies and provided a detailed analysis of the existing literature on the topic. Key findings include:

- Prevalence & Recognition: Despite its rising frequency, CVA remains an under-acknowledged form of maltreatment.

- Terminology & Measurement: The ACE Questionnaire and the Conflict Tactics Scale stand out as primary tools for evaluating CVA.

- Perpetrators & Definitions: Parents, particularly mothers, followed by teachers, are the primary caregivers whose language has been reported to contribute most significantly to ACES. The nature of CVA centers around speech volume, tone, and negative content.

- Outcomes & Consequences: CVA results in lasting emotional and behavioral outcomes. It's essential to recognize its unique characteristics for proper prevention and intervention.

- Recommendations for Prevention: The study champions trauma-informed approaches and emphasizes the role of adult training in promoting safety, support, and nurturance during interactions.

Educators, parents, and practitioners (e.g., teachers, coaches, directors) can make a substantial difference in children's lives by understanding these intricacies. We can support these efforts by reviewing theoretically and empirically supported practices that we know work.

- Teaching Expectations and Skills: Clear expectations form the backbone of effective education and mentorship. Teaching, modeling, and reinforcing behaviors and skills offer a clear roadmap. Teaching behaviors can resemble direct instruction, which involves showing, telling, and doing. It can also incorporate role-playing to enhance learning, and consistent feedback and behavior-specific praise solidify these lessons.

- Preventing Problem Behavior: Being proactive is essential. Encouraging desired behaviors through positive reinforcement can yield significant results. Strategies like precorrection and active supervision can remind children what the expectations are before going into a challenging situation, while also increasing active supervision during that transition or situation can further facilitate children’s success!

- Responding to Behavior: Proper responses are as essential as teaching expected behaviors. Celebrating children for meeting behavior expectations and addressing undesirable actions with care and guidance fosters an environment of growth. Reinforce positive behaviors and re-teach and use logical consequences when problems arise. As adults we should respond to challenging behavior by clearly articulating what desirable behaviors we hope to see instead. This focus on what we want to see minimizes the chance that children will experience a negative experience from always hearing what they are doing wrong.

- Trauma-Informed Approaches: Tailoring our interactions to be trauma-aware ensures that children feel secure, cherished, and understood. The crux of this approach hinges on safety, support, and nurturance. Parents and teachers alike should involve children in behavioral reflection when challenges arise. Wait until the child is in a calm state and then discuss things that contributed to the behavior (e.g., unmet needs, lacking skills), describe the behavior, and possible consequences (i.e., effects of the behavior on themselves, peers, and adults). Use a restorative lens to focus on what to do differently going forward rather than condemning the child for choices made in the past.

- Adult Training: Comprehensive training modules can teach adults to recognize their unconscious biases, control reactive behaviors, and approach children with patience and empathy. By enabling adults to adopt trauma-informed perspectives, we create environments where children feel understood, valued, and protected. Training should emphasize the importance of adults as models of social/emotional regulation. Adults should seek to narrate as they process through their own emotions. Adults should also model apologizing or engaging in restorative practices when making mistakes.

In conclusion, while our efforts to combat childhood traumas, especially verbal abuse, are ongoing, with dedicated research, effective training, and community engagement, we inch closer to a world where every child flourishes in a nurturing environment.

Reference

Dube, S. R., Li, E. T., Fiorini, G., Lin, C., Singh, N., Khamisa, K., McGowan, J., & Fonagy, P. (2023). Childhood verbal abuse as a child maltreatment subtype: A systematic review of the current evidence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 144, 106394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106394

The State Complaint Procedure

Mitchell Yell

When we think of parents filing complaints against school districts regarding special education services, we usually think of mediation, resolution sessions, due process hearings, and possible court cases. However, there are additional, less well known, complaint resolution systems that the parents of students with disabilities may use.

The IDEA includes requirements regarding mediation, resolution sessions, due process hearings, and court cases but does not address state requirements for developing and implementing a state complaint procedure (SCP). Nonetheless, the U.S. Department of Education has determined that states must development, offer, and implement a SCP system. According to the U.S. Department of Education in 2006, “we believe that the State complaint process is fully supported by the (IDEA) and necessary for the proper implementation of the Act and these regulations” (Federal Register, 2006). Therefore, the SCP process is written into the regulations implementing the IDEA. The regulations to the IDEA require each state to establish and implement written procedures for resolving any complaint that meets the definition of a state complaint set forth in the regulations (IDEA Regulations, 34 C.F.R. § 300.151[a][2]).

Information on your state’s SCP can most likely be found on the webpage of the state’s special education office or department. State’s SCP must be communicated widely to parents and others by including information on the complaint process in the procedural safeguards notice provided to parents, (IDEA Regulations, 34 C.F.R. § 300.151[a][2]).

Filing a state complaint usually requires that a parents or other organization go online and find the state’s SRP and then submit a formal complaint reporting a possible violation of a student’s special education rights and requesting that the state investigate the issue. The complaint is also sent to the school district (called the local education agency or LEA). State personnel are then responsible for investigating the complaint and deciding about the legitimacy of the complaint.

Regulations to the IDEA require that the complaint filed with a state must include (a) a statement that the school district has violated the IDEA, including the facts on which the allegation is based; (b) the signature and address of the person or organization filing the complaint; (c) the name and address of the student and the name of the school he or she is attending; (d) a description of the problem the student exhibits; and (e) a proposed solution (IDEA regulations, 34 C.F.R. § 300.153). States are also required to develop forms for filing state complaints, although parents are not required to use such forms. Parents, or organizations may file complaints, however schools may not.

State complaints must be filed within 1 year of the alleged violation. Although states may increase this statute of limitations, states cannot shorten the statute of limitations (OSEP, 2009). So, for example, if a parent had an issue with a school’s provision of a FAPE during the 2020 to 2021 Covid pandemic, it may be too late to file a complaint now (in September 2023).

After a state complaint is received, if state officials determine that a full investigation is necessary, then the investigation must be conducted onsite. The SEA has 60 calendar days from the date the complaint was received to conduct its investigation and issue the written decision unless extenuating circumstances exist. The regulations to the IDEA specify two allowable reasons for extending the 60-day time limit for the CPR resolution. Under the SEA may extend this time limit only if: (1) exceptional circumstances exist with respect to a particular complaint; or (2) the parent is engaged in mediation or in another alternative means of dispute resolution, which are available under a state procedures and the involved school district officials agree to extend the time to engage in mediation or other alternative means of dispute resolution (IDEA Regulations, 34 CFR §300.152[b][1]).

When investigating a school district, state personnel must review all relevant information and make an independent determination as to whether a school has violated a requirement of the IDEA. State personnel must allow personnel in the school district to respond to the complaint. Additionally, a parent must be given an opportunity to add additional information or to amend a complaint. Moreover, voluntary mediation be offered to both parties involved in the complaint (IDEA Regulations, 34 C.F.R. § 300.152[a][3][ii]). Following the investigation, the SEA must issue a written decision that addresses each of the allegations in the complaint and include findings of fact and conclusions, and the reasoning behind the final decision.

If the SCP ends with a decision that a school district violated the IDEA, the SEA must address the failure of the school district and prescribe corrective remedial actions (IDEA Regulations, 34 C.F.R. 300.151[b][1]). Such remedial actions could include compensatory services, monetary reimbursement, and appropriate future provision of services for all students with disabilities (IDEA Regulations, 34 C.F.R. § 300.151[b][1]). States have broad flexibility to determine appropriate remedies to address the denial of appropriate services to an individual child or group of children and usually may award any remedy for a violation that a court or hearing officer may award. The final report completed by state personnel must also include procedures to assist school districts to effectively implement the SEA’s corrective actions, which may include technical assistance activities and actions to achieve compliance.

If a school district fails to implement a corrective action related to the state complaint, parents have the option to file a request for due process hearing on the same issue as alleged in the state complaint. But before resorting to the due process hearing option, parents are encouraged to work with the school district to implement the corrective actions in the state complaint. Whether the state’s resolution of a complaint is subject to appeal to a state or federal court is a matter of state law. Hearing officers do not have the jurisdiction to review or enforce the state’s SCP, nonetheless, a state’s decision in the SCP is enforceable in court (Beth V. v. Carroll, 1996).

A great source of information on the SCP are the following two documents: Dispute Resolution Procedures under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act published by the Office of Special Education Programs in 2013, and “IDEA Special Education Written State Complaints” developed by the OSEP-funded Center for Appropriate Dispute Resolution in Special Education or the CADRE center in 2014.

My Most Memorable Student: Voices from the Field – Marilyn Kaff

Jim Teagarden & Robert Zabel, Kansas State University

The Janus Oral History Project collects and shares stories from leaders in education of children with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD). The Project is named after the Roman god, Janus, whose two faces look simultaneously to the past and future.

One Janus Project activity is recording and sharing educators’ descriptions of memorable students. They are asked: Who is your most memorable student? What did you learn from this student? How has the student impacted your career or life? What follows is Dr. Marilyn Kaff’s story of Ray.

* * * * *

I’d like to tell you the story of Ray. Ray was a 3rd grader, and a chronic whiner. Every day he would complain about something. Ray was the kid that who’d go out to recess and try to run to the basketball game. All the boys would just go, “Yuck.” He was so annoying.

One January afternoon, Ray came in from recess. He had jumped out of the swing and was moaning, “Oh my arm hurts.” He’d been warned not to jump from the swings, but he did anyway. I sent Ray to the school nurse, who was aware of his tendencies since he’d often shown up in her office. The nurse looked at his arm, found nothing, and sent him back to the classroom. Ray continued to complain about his arm, so I sent him back to the nurse. She’d send him back to the classroom, and I’d send him back to her…this routine went on 3 or 4 or 5 times. Ray continued to complain about his arm, and we’d tell him that he’d be fine. We told to lay down and he’d be fine.

Of course, that was the one time that we didn’t listen to Ray. When he went home, his mother took him to the Emergency room, and discovered that he had a hairline fracture. The lesson that I took from this experience with Ray is always listen to the kids. They’ll usually steer you in the right direction.

* * * * *

Dr. Marilyn Kaff is an Associate Professor of Special Education at Kansas State University. Her story about Ray is a part of the Midwest Symposium for Leadership in Behavior Disorders video series, “My Most Memorable Student.” It is available for viewing at: https://archive.org/details/MarilynKaff302. More than 40 stories of memorable students can be viewed at: http://mslbd.org/what-we-do/educator-stories.html

Dear Miss Kitty: Advice Column

Miss Kitty

Dear Miss Kitty:

I was a teacher of students with emotional/behavioral disorders for six years and a job opening as a general education teacher was posted and I decided to make a switch to a 4th grade classroom in the same building. The district could not find a full-time teacher to take my place so the principal put the students in my general education classroom because he said: “You are a certified special education teacher so you can take the students since we can’t find anyone.” Now I have 7 more special education students in my fourth-grade general education classroom, and they are 4th, 5th, and 6th grade.

I told the principal I shouldn’t have the students because that is a violation of their IEPS which called for only 40% of their time in general education. He says I should be able to do this because I am credentialed in special and general education. Is this right? I am feeling overwhelmed because I now have 27 students in my class and the special education students have many needs. Also, it is only October and some of the parents of the general ed students are asking why a 6th grader is in my 4th grade class.

Overwhelmed Oscar.

Dear Overwhelmed Oscar:

Thank you for writing and I am sure you are feeling overwhelmed because you are being expected to do two different jobs in one day. I do hope you have a paraprofessional to assist you but that does not solve this serious problem you are facing. If their IEPs were not reconvened to change them, this cannot be done. The rights of the students and their families have been violated. The students are not getting the services that they are legally supposed to get.

Have you spoken to the principal and asked him what he is doing to find a special education teacher? Yes, we all know there is a shortage of special education teachers, but these children deserve someone who can devote his or her time to these students. Has a substitute teacher been considered until a full-time special educator can be found? Can they find a part-time teacher? These are all possible options you will want to discuss with the principal.

If you cannot come to a resolution with the principal, do you have a teacher organization in your district that you can approach? Your contract would say that you were hired as a 4th grade teacher so that contract needs to be honored. I hope your teacher organization can help you.

If you have tried all these options and there is still no resolution, you do have an obligation to report what is happening. Your children’s rights are being violated. See if your professional organization like DEBH can assist you or tell you where to get help. Explore what process your state department of education has for filing a complaint and how you can file one with them. Also familiarize yourself with advocacy agencies like funded special education parent training centers and enlist their assistance.

I hope this helps and thank you for standing up for your students and their families.

Recreational Reinforcement is a column highlighting educators' and professionals' recreational and leisurely pursuits while making connections and offering illustrations and examples related to applied behavior analysis. This month’s column explores applied behavior analysis (ABA) and pumpkin spice blend.

Keywords: pumpkin spice blend, principles, applied behavior analysis, lattes

2023-2024 Call for Columns:

Recreational Reinforcement is a bi-monthly (6/year) column dedicated to discussing recreational or leisurely pursuits, making connections, and offering illustrations and examples related to applied behavior analysis. The only rule is nobody wants to hear about work being your “recreational reinforcement.” Please send submissions or inquiries to Dr. Eric Common at ecommon@umich.edu. Directions for submissions: (a) article title, (b) names of author(s), (c) author’s affiliations, (d) email address, and (e) 700-1500 word manuscript in Times New Roman font. Bitmoji, graphics, tables, and figures are optional.

Ah, dear readers! As the autumn leaves begin their majestic dance, many readers sip pumpkin spice lattes and nibble on pumpkin pastries, or even pumpkin pie. Originating from the 1700s and 1800s kitchens, pumpkin spice was the secret behind many a pie that warmed the hearts during chilly evenings. This blend was the essence of American baking traditions, often combining the robust flavors of cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and cloves.

Now, as begin the autumn season, let's take a moment to appreciate the wonders of applied behavior analysis (ABA). Surprised? As pumpkin spice has evolved, so has our understanding of behavior. Whether it's the choice of spice mix, the allure of a frothy latte, or the temptation of a seasonal treat, it's fascinating to see ABA principles at play. After all, every sprinkle of spice or sip of latte can offer insights into our behaviors and choices.

We spotlight in this article some principles of behavior, offering definitions and illustrations of pumpkin spice in the context of behavior.

| Principle | Description | Pumpkin Spice Blend Example |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior is Observable and Measurable | ABA emphasizes the importance of focusing on overt behaviors that can be observed and measured rather than internal processes such as thoughts and feelings. | Observing and measuring the frequency of customers purchasing pumpkin spice blends at a store during the fall season. |

| Environmental Influence on Behavior | Environmental variables significantly influence behavior. This includes antecedents (events preceding a behavior) and consequences (events following a behavior). | Antecedent: A store displays pumpkin spice blend prominently at the entrance during autumn. Consequence: Increased sales of the spice blend. |

| Reinforcement | Refers to the aftermath of a behavior in an ABC (Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence) contingency that heightens the likelihood of the behavior recurring. Maintaining consequences can involve gaining or avoiding attention/social interactions, activities/tangibles, and sensory experiences. | After baking a pumpkin pie, a person receives compliments and is told not to help with the dishes, which increases the likelihood they'll bake it again. |

| Punishment | Refers to the aftermath of a behavior in an ABC contingency that reduces the likelihood of the behavior happening again. Positive punishment involves adding something, while negative punishment involves removing something. | Positive Punishment: Adding extra pumpkin spice to a pie makes it too spicy and reduces the likelihood of adding so much next time. Negative Punishment: Forgetting to add pumpkin spice to a latte, resulting in a bland taste and the decision to always check ingredients before serving. |

| Functions of Behavior | Behaviors are either reinforced or punished based on gaining access to or escaping from: 1) Attention (social), activities/tangibles, sensory experiences 2) Escape from attention (social), activities/tangibles, sensory experiences. | After baking a pumpkin pie, a person receives compliments (positive reinforcement: social attention) and is told not to help with the dishes (negative reinforcement: activity), which increases the likelihood they'll bake it again. |

| Generalization | Skills or behaviors learned in one context or with a specific set of stimuli should be applicable to other contexts or stimuli. | After learning to make pumpkin spice pudding at home, a person uses the same skills to make other pumpkin-spiced desserts. |

| Socially Valid | ABA targets behaviors that hold social importance, aiming for socially appropriate goals/effects and outcomes that can enhance the individual's quality of life. | Introducing pumpkin spice blend in recipes during a community potluck, as it's a socially popular flavor, leading to increased consumption of your dish, and general merriment of all. |

While reviewing the basic principles of ABA let's not forget the basic spices of pumpkin spice blend. For those eager to whip up their own blend, here's a simple recipe: 4 parts cinnamon, 2 parts nutmeg, 1 part ginger, and a pinch of cloves. Voilà! Your very own homemade pumpkin spice blend. Many of us enjoy the flavors that pumpkin spice brings with the season and find it a very welcome part of fall. If you are one of the readers who do not enjoy pumpkin spice and find it to be an aversive part of the season, there are many comedic resources that you can enjoy about the season as well. Whether you enjoy pumpkin spice or the comedy that pumpkin spice brings, enjoy the fall season!

Authors Bio

Eric Common is an Associate Professor at the University of Michigan-Flint in the Department of Education and is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst at the Doctoral Level

Erin Fitzgerald Farrell is an Adjunct Professor at the University of St. Thomas in the Department of Education and is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst